Hall of Fame Inductees:

- Bernie Schreiber

- Manuel Soler

- Rob Shepherd

__________________

Trials Legend – Bernie the First

The only American to win a world trials championship, with his pivot turns and bunny-hops California’s flamboyant Bernie Schreiber was a god-like figure to a whole generation of young riders, changing the face of the sport…

Words by Sean Lawless

Photos by: Iain Lawrie, Kinlochleven; John Honeyman; Chris Sharp Photography; Stephen Postlethwaite; Blackburn Holden III; Alain Sauquet; Eric Kitchen; Fin Yeaman; Len Weed; Claudio Pictures (Jean-Claude Comeat); Jean Caillou.

Main photo: Eric Kitchen copyright

This article first appeared in Dirt Bike Rider Magazine, March 2018.

I was a spoilt brat when I was a kid. When your old man’s the Editor of Trials and Motocross News you get all the best machinery and all the best kit – bikes that are still in a developmental stage, the latest line in Ellgrens – but the one thing I wanted more than anything else was a pair of Bernie Schreiber-signature Alpinestars.

I was nine years old when Bernie won the FIM World Trials Championship and to me – and most of my trials buddies – he was the man. Tall, handsome and with style for miles, he had the same aura of California coolness that the likes of Bob Hannah and Broc Glover exuded. Sure, I had lots of role models from much closer to home to choose from but mighty Martin Lampkin – who lived less than sixty miles away – or Finnish iceman Yrjo Vesterinen didn’t capture my imagination in the same way as the alluring American did back in 1979.

Sadly, I never did get those boots – I’d never have been able to fill them anyway – but by way of consolation I did get to spend a couple of very enjoyable hours on a Skype call with him back in January after he responded to my friend request on Facebook.

Now living in Zurich with his wife – a tax lawyer with a consulting powerhouse company – and their young son, Bernie may have moved away from his home state the best part of forty years but he still possesses that laidback, easy-going SoCal cool.

“I grew up in Los Angeles and I had a paper route after school for quite a few years,” he says. “I was riding a Stingray bicycle and we had a lot of hills and I always enjoyed trying to do wheelies down them. I only had a brake on the back so I’d just balance. My father noticed that I liked bicycles a lot – besides for just delivering papers. There were some hills behind the house and I’d build a little ramp to make a jump. I just liked being on two wheels.”

When I think of SoCal in the ’70s I automatically think of motocross although, to be honest, if I think of SoCal in the ’80s, ’90s and beyond the last thing I would think of is trials. So how did Bernie – the greatest trials rider America has ever produced and a genuine icon of the sport – get involved in the first place?

“My first motorcycle was actually a Kawasaki 90 and we used to go riding in a place out in the desert called Little Rock. A friend of my father’s told us about it so we went there and one day this friend came out and his son was riding around in a circle standing up and I didn’t know what that was! We asked what he was doing and were told that he was practising for a trial at Saddleback Park.

“So I went down to Saddleback and there were quite a few kids – one of them was Jeff Ward whose father was out there riding trials as well in the adult class. I rode the Kawasaki – I had footpegs on the back so I tried to stand up on those to see if I could lean forward riding up the hills and I kinda liked it.”

It’s no surprise to discover that Bernie was a natural and he quickly progressed. Moving up to a 125cc Bultaco, he was soon competing against adult competitors despite being barely into his teens.

“I got a little deal on a bike – the first Sherpa T250 – and I started doing much better. I was in the Amateur class, then the Expert class and at that time they had the Master class – that was the first time we went to the El Trial de Espana where I got to see Sammy Miller for the first time. That was a big deal – I think it was back in 1972 or ’73.”

El Trial de Espana, an annual event started by US Montesa importer Fred Belair, doubled up as a fund-raiser to send young riders across to Europe and to this day remains a major event on the SoCal trials calendar.

“About a year later there was a trials school with Mick Andrews in California. Sammy and Mick were the two riders who impressed me most – especially Mick. They were the role models for me at the time. Then they had the world round in the US at Saddleback Park in 1974 – it was really muddy and I got to ride with an X on my bib because I was under eighteen.

“There was Alan Lampkin and Martin Lampkin – not too many riders came from Europe, I think there was maybe ten of them – and I actually did quite well and finished it better than any other American rider.”

At the time only a rider’s best seven results from the thirteen-round series counted which explains the poor turn-out of European riders. Bizarrely, it was also actually a round of the FIM European Trials Championship which had crossed the Atlantic for the first time in preparation for the inaugural full world championship the following year.

Because of his age Bernie doesn’t feature in the results from Saddleback but his finish would have put him at least in the top eight – not bad, even given the limited European presence, for a fifteen-year-old.

“El Trial de Espana sent a delegation to Europe to watch the world rounds and when they came back there were a couple of people who also set up trials events and they made them a lot harder for the Master class. They tried to make sections similar to what they saw in Europe.

“I won the trip to go there once and then I won it a second time when I was under eighteen – I went one time to Barcelona and saw the world round and visited the Bultaco factory. Then I went back again for the Scottish in, I think, 1976 which was when I rode Charles Coutard’s bike. I took it as a spectator because he’d broken his wrist so I changed into his clothes and rode the Ben Nevis sections.”

At the time, Southern California was the epicentre of US trials and the Schreiber household played host to a four-time Spanish champion who was keen to mix business with pleasure.

“I was riding the national championship and Bultaco came to visit me. Manuel Soler came and stayed with us for a while and we rode together. I think he came for the experience to visit Los Angeles but also to see how I was and to report back to Bultaco. I was kinda scouted out.”

Then came the game-changer that would alter the course of Bernie’s life…

“I was sponsored by a local dealer – Steve’s Bultaco – who were just providing a bike and then the importer at that time, John Grace, flew out from West Virginia to visit me and my father and asked if I’d like to compete in the world championship. They wanted to give me the chance to go out to Europe and ride with the rest of the Bultaco team in 1977 to see how it went and I finished in the top ten almost every event.

“If my results had have been bad I’d have probably never seen them again. To be honest I didn’t think I was going to stay. It was quite tough for me – we didn’t have all the fancy stuff that these riders have today – and travelling was a different thing back then.”

He initially moved to Belgium and then Spain but the factory figured its American hotshot would feel more at home speaking a language he understood so Bernie relocated to England where he spent two years living with Pete Hudson – the Competition Manager for UK Bultaco importer Comerfords – and his family at West Byfleet in Surrey.

“I was working in the shop a little bit, helping to set up bikes and doing things like that in between the season otherwise it would have been quite difficult so they really supported me but it wasn’t so easy times for the brand because Bultaco had already started to have difficulties by 1978.

“Still, it was really an adventure. A lot of fun but always wet, always raining – I used to joke that I had a lot of friends in the UK and told them to call me when the sun came out but I never heard from them again!”

Vesterinen took his second title in 1977 but Bernie’s eventual seventh-placed finish with podiums in first Spain and then Germany showed huge potential. Vesty then clinched his hat-trick of titles in 1978 but Bernie matched him win-for-win and finished just twelve points behind in third place. The scene was set for his historic 1979 campaign…

Bernie celebrated his twentieth birthday three weeks before the opening round in Northern Ireland where his championship got off to a bad start when a big crash and subsequent bent forks handed him a DNF and no points. A seventh second time out in Rhayader at the British round – twenty marks behind winner Malcolm Rathmell – wasn’t a lot more promising, nor was sixth at round three in Belgium.

A week later in Holland, Bernie claimed a fourth before winning in Spain. It was the start of a run of six consecutive podiums – including further wins in the USA and Sweden – while his rivals struggled with consistency. With two rounds to go it was a two-horse race with Bernie leading the defending champion by nine points but, at the penultimate round in Finland, Vesty slashed the deficit to just three points as he came home third while Bernie slumped to seventh.

The title was decided at Ricany, around fifteen miles south east of Prague in the Czech Republic. With the pressure on, Bernie rode out of his skin to drop just thirteen marks – the lowest score of the season and also the biggest winning margin – with Ulf Karlson nineteen marks further back in second.

“I was excited to win. I was excited for Comerfords who had supported me, I was excited for my parents and of course for the Hudson family who had also supported me when I was living there. That win was important for me – not as an American or a non-European, I was just happy to feel like I was the best rider.

“The reason I say that is because I was competing against Martin Lampkin who had been world champion in 1975 who was on Bultaco, then I had Vesterinen who was a three-time world champion on Bultaco, Manuel [Soler] was on Bultaco – we were on the same bike so in the end it was kinda the best rider won.

“There were no question marks and I was happy about that, even if it was just one time.”

With his first world title in the bag, what Bernie did next seems crazy – he jumped ship and signed to ride for Italjet. Although the Italian manufacturer had been around for over twenty years and had enjoyed success in small-capacity road racing, its trials project was still in the fledgling stages but pressing financial concerns – along with the wave of confidence he was riding – persuaded Bernie to make the move.

“Signing for Italjet is always a question mark that comes up in my career. Why did I go there? There are reasons for that. Leopoldo Tartarini at the time was the importer for Bultaco in Italy – he saw the situation coming and he thought he could take over.

“At the time I left Bultaco I didn’t get paid for three months – I never got my championship bonus because they were insolvent and I was a rider, an external consultant – so I had no financial means. He made an offer and I took that risk. I didn’t have so many financial offers and he made a lot of promises – what they were going to do, bring the team and bring the mechanics. They were going to try and bring Bultaco back in another way so I took that risk and went to Italjet.

“You think ‘okay, you’re the best in the world’ so the bike doesn’t really matter, the equipment doesn’t matter. I moved to Bologna, I started to learn Italian – it was an experience. The problem was that I was a rider, I wasn’t an R&D person. I could test ride things but I was interested in riding, I was interested in winning – I wasn’t interested in going out and giving feedback on how to develop the best bike in the world. They thought they could just develop whatever they wanted. They thought ‘Bernie can win on anything’.”

Tartarini is a famous figure in Italian motorcycling. The son of a road racer, he also raced professionally and – despite once turning down a factory ride with MV Agusta because his mother wanted him to manage the family motorcycle dealership – achieved considerable success. When he became disillusioned with selling bikes for other manufacturers, the family started Italjet in 1959.

“He was a nice man but it just didn’t work out. His expectations were ‘I can make whatever I want and you do whatever I tell you to do’. He was very supportive but at the end of the day it didn’t work. In the beginning we called it a Greentaco – a Bultaco painted green – and during that first year there was a prototype stage of making some modifications and at one point that bike really was one of the best bikes in the world but it was a one-off model.

“I said ‘let’s just keep that, look at Honda they have one prototype’ but then they tried to make a production bike which was totally different and that’s when we started to have some problems.”

Bernie had to wait until the fourth round of the 1980 championship before he took his first win of the season and was back on top of the podium at round six. He then suffered no-scores in Switzerland and Germany due to mechanical problems before sweeping the final four rounds but ended the year second, ten points behind Karlson.

For 1981 Bernie was mounted on the production bike and struggled to sixth with both inferior machinery and a lack of motivation.

“It was a really tough bike to ride – it was very stiff, it was heavy, it had Pirelli tyres instead of Michelin and it was just not a good year for me. I was not motivated anymore. I think I had a few podiums but my only dream was to have again a proven, winning bike.”

After winning the 1981 title, Burgat left SWM for Fantic. Bernie picked up his ride and stayed there for three successful years, finishing runner-up in 1982 and ’83 and third in ’84.

“It was a good bike and I really enjoyed my time at SWM. We had Martin Lampkin on SWM in ’82 and at the time they were developing the Jumbo especially for Martin because he was aggressive and he was strong and the 320 just didn’t have the power for him. I think if I would’ve worked more on that 320 rotary Rotax engine instead of moving to the Jumbo…

“Instead I had to change to a completely new product and that was difficult. Eddy Lejeune was coming strong and he had a lot of support from Honda and his family and it was tough for me – I was isolated in Italy and I never had that kind of support. He had his younger brother, his older brother, his father – he had money, Honda had money, he had a training programme.

“I don’t want to give a lot of excuses but the sport had started to change. It became more of a team sport than an individual sport and that was a complete change.”

Bernie won two rounds in 1984 – in Great Britain and Germany – to take his victory total up to twenty but his win in Osnabruck was the last time he’d top a world championship podium.

“At the end of ’84 SWM sold everything to Garelli – the team, the people – and at the time everyone was going to monoshock and we were still making twin-shock trials bikes. I rode two events, they told me I wasn’t focussed, I told them the bike was shit and we got into a dispute about that.

“I told them ‘no problem, we can just rip up the contract and stop right now or I can continue and try and finish in the top fifteen and you can keep paying me for shitty results which I think is not good for you’. I also told them I wasn’t going to rip up the contract and then sit at home and couldn’t guarantee that within a couple of months I wouldn’t be riding some other brand and then we would see if it was the rider or the bike.

“They said ‘no, we don’t want that, we’ll just pay you and you do nothing for the rest of the year – go on vacation until the contract terminates’. I said ‘that’s fine with me, have a nice day’ and that was the end of the story.”

In 1986 Bernie joined Gilles Burgat on Yamaha, ending the season seventh with a best finish of fifth in Sweden, before a switch to Fantic for 1987 netted him his fourth and final US title. He also scored points in the two world championship appearances he made but Bernie’s priorities lay elsewhere…

“I really enjoyed riding the Yamaha. It was a good bike – a lot of fun – and I got some pretty good results. I won some events – not world championship rounds – and really enjoyed riding. I also really liked the Fantic but that was kinda the end. I was teaching trials and doing some other things.”

It’s perhaps fitting that Bernie, a rider who did so much to stamp his own flamboyant style on world trials, called time on his career just as Jordi Tarres – who won the first of his seven world titles in 1987 – was spearheading a new era in the sport.

While many top professionals continue to ride at a lower level after retirement, Bernie really did quit the sport – although he staged a one-off comeback ride on a Bultaco at the 2008 Robregordo and in 2011 in a two-day classic trial in France, competing against old foes including Vesty, Coutard, Bernard Cordonnier and Soler.

“I hadn’t ridden a trials bike for years and they threw me an SWM Jumbo – I think they’d even cut the flywheel down so as soon as you turned the throttle the thing hit you in the head! It was a little bit difficult at first but it was fun and after one or two laps I started to get the feeling back.”

Pete’s perspective

Living with Bernie…

Thank you to www.retrotrials.com for allowing us to publish this excerpt from a piece written for the website by Pete Hudson, Bernie’s former Competition Manager at Comerfords.

“I remember this young lad of 17 came over to Comerfords from America. He didn’t have anywhere to go and didn’t have anywhere to stay. He had come over with Marland Whaley and Len Weed to do the world rounds. He was a bit upside down and didn’t know where he was going so I took him home.

“My two boys just idolised him. He was like an older brother to them. Of course, Bernie would go off to the factory and then come back and we would go off in the van here there and everywhere. I would take Colin Boniface and Peter Cartwright as well to some of the rounds.

“I really just tried to keep Bernie’s head on. Although he was a quiet boy off the bike, on the bike Bernie was flamboyant and would play to the crowd. He could do all of the tricks and he liked to show people that he could do them. Bernie was the first one to do the pivot turns – riding on the balls of his feet instead of the insteps – and bunny-hopping.

“When I saw him doing this I remember thinking ‘trials is on the change, this is really different’. He got a lot of basic coaching from a bloke called Norm Sailer at a ski lodge in Donner Pass in North California. He got a lot of influence from this guy.”

“Bernie lived with us for two years and, of course, became part of the family. Bernie just wanted to progress and progress – he’s a world champion, that’s what world champions do.”

US of nay!

America’s trials tribulations…

In 1979 Bernie was the youngest ever motorcycling world champion in the FIM’s history but while he got lots of coverage in the European specialist press, back home – then as now – trials didn’t command the headlines.

“Those were good days for the Americans. We had Kenny Roberts, we had Brad Lackey, we had the speedway rider Bruce Penhall – there were a lot of great riders and champions coming out of the United States in those days so the American press had plenty to talk about besides a trials rider.”

This disinterest certainly contributes to why Bernie remains the only world trials champion to be produced by such a great motorcycling nation but he feels there are other factors involved.

“I’m disappointed there’s no other US riders but I’m not surprised. I just don’t think they have the system or any desire. Trials in the US is very small. You have the NATC [North American Trials Council] and then you have the AMA [American Motorcyclist Association] and the AMA never really supported trials ever in the history of the sport in the United States. They never did anything for me.

“The NATC (AMA) were trying to grow the sport but based on their philosophy that Americans are different and we have to do the sport in our own way and it’s about having fun and we don’t want to make sections too difficult and maybe that was best for the sport.”

But it’s not just the US that’s taken a back seat in trials – the record books tell a tale of almost complete European domination with only Japan’s Takahisa Fujinami able to break the stranglehold on one other occasion.

“Until 2004 in the history of the sport I was the only non-European world champion. Nobody really talks about it from that perspective – I don’t think anyone has probably thought about it.”

Career highlights

Don’t forget the SSDT!

While the 1979 world title was undoubtedly the highlight of his career, Bernie’s list of accolades is long and illustrious and includes four AMA titles (in 1978, ’82, ’83 and ’87) plus a string of indoor wins and victories in other high-profile events.

“Winning the Scottish Six Days [in 1982 and the only non-European to do so] was very important – people used to tell me that if you hadn’t won the Scottish then you hadn’t won anything, especially in the UK. Then you had to win a British world round [he won twice, in 1982 and ’84] because that had meaning. There was quite a bit of stuff like Kickstart and I won lots of indoor rounds but they didn’t have it as a championship back then.”

Bernie was inducted into the AMA Hall of Fame in 2000 and in 2004 was one of the first five inductees in the NATC Hall of Fame.

Life after trials

What Bernie did next…

“I’ve been an ex-pat for forty years. My wife’s from Lithuania – we’re both ex-pats – and we decided Zurich was a good place for our family. My two daughters are in Europe so I’m not going back to the US and, besides, I like Switzerland.” [Bernie has dual US/Swiss nationality]

Since retiring from trials his professional life has remained every bit as colourful as his sporting career and he’s moved from one role to the next, always looking for something that is challenging, stimulating and entertaining.

“I worked for a lot of manufacturers – I did some project development stuff whether it was for Alpinestars or Yamaha or Michelin. I did a lot of different things. I wrote a book with Len Weed so I kinda became almost an author.

“Then I had to do a transition into business so I started those trial schools and then I got involved with Malcolm Smith.”

Alpinestars was importing Malcolm Smith products into Italy and through that connection Bernie started working for the Italian company before starting his own company in France – Schreiber Group Europe – which he ran for six years making, among other projects, his own mountain bikes, Kamikaze.

“I was doing all kinds of stuff. Helping US companies – Answer products, Manitou forks, all these products – set up distribution. So from 1992 to 1997 I was basically running my own company and doing all kinds of services with bicycle companies and some motorcycle stuff and then I got involved with Tissot and they asked me to come and work full-time internally. My company was small, I didn’t have a lot of experience so I thought going to work for a big multi-brand, multi-national group was a great opportunity.”

Bernie moved to Switzerland and spent the next ten years working for Tissot watches which, along with around twenty other watch brands including Omega, is owned by the Swatch Group.

“During that time it grew from a 100 million turnover into a billion dollar company and the sponsorship didn’t exist so everything that was built there that you see today basically I was involved in – everything from ice hockey to cycling.

“When I first got there they were involved with the UCI [Union Cycliste Internationale] – they’d signed a timekeeping agreement but that was the only contract they had at the time. We went from there and took MotoGP, got involved in supercross, motocross, ice hockey, fencing, NASCAR, we had athletes like Michael Owen. I personally signed Nicky Hayden two weeks before he won the world championship.

“After ten years I had a career break – that was enough for me. I met my future wife and decided to move on. Then my son was born and that changed everything. I took a break for almost a year-and-a-half – then I had a call from the CEO of the whole Swatch Group who sent me to the US for three years on this golf project.

“It was a fabulous opportunity – I got to work in a huge industry with Omega – and I had a great time and met a lot of great, very interesting people.

“When I came back to Europe the president of Omega left the company, the management completely changed, I was commuting an hour-and-a-half each way to work each day and decided that it was time for me to move on so I left Omega at the end of 2016.”

“In 2017 I was involved in some projects with e-mobility bikes and 2018 working with Ryan Pyle an outdoor TV adventure. In 2019, I celebrated the fortieth anniversary since my world title and was my comeback year riding Classic events and executing Trials schools.”

“2020 will be a surprise with new and interesting developments on the horizon. Promoting the sport for all is my focus.”

© Article Text: Sean Lawless/Lawless Media UK – 2019.

Bernie Schreiber facts:

WORLD TRIALS RANKINGS SUMMARY:

| YEAR | WORLD RANKING | MOTORCYCLE |

| 1977 | 7 | Bultaco |

| 1978 | 3 | Bultaco |

| 1979 | 1 | Bultaco |

| 1980 | 2 | Italjet |

| 1981 | 6 | Italjet |

| 1982 | 2 | SWM |

| 1983 | 2 | SWM |

| 1984 | 3 | SWM |

| 1985 | — | Garelli |

| 1986 | 7 | Yamaha |

| 1987 | 20 | Fantic |

“A GOAL without a PLAN is nothing but a DREAM” – Bernie Schreiber 2019

___________________

TRIALS LEGEND:

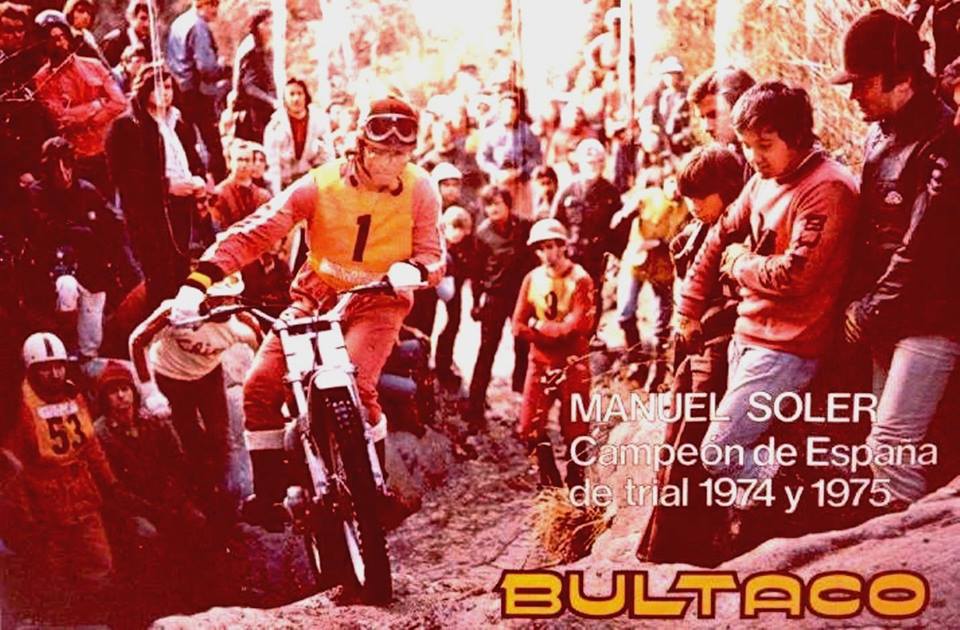

Manuel Soler 1957-2021

Manuel Soler Alegre was born on March 9th, 1957 the son of Juan Soler Bulto, the nephew of Senor F.X. Bulto who created the Bultaco brand. Manuel Soler was to grow up in the motorcycle industry and become a development rider for the San Adria De Besos Bultaco factory and a supported international trials rider.

Soler rode in many countries during first of all the European and then the FIM World Trials Championships. He became the first Spanish rider to win a world championship round on a Bultaco.

During his time with the family company, Soler was responsible for testing the Sherpa models and preparing written reports from test sessions and events that he competed in. This feedback was used by the factory to make improvements, year by year.

He was the only employee/family member to have a Bultaco model named after him, the 1975 M158/159 Sherpa ‘Manuel Soler’.

His special factory prototype M159 was used in publicity material by the factory publicity department.

We are fortunate to be granted permission to reproduce an interview with Manuel Soler, conducted by Horacio San Martin for his excellent Spanish trials website ‘Todotrial’ in 2019.

Interview with Manuel Soler – March 8th 2019

Words: Horacio San Martin of TODOTRIAL.com

Article reproduced by kind permission and Copyright of Todotrial.com

After listening to him speak about the 50 years of the Spanish Trial Championship “Championship Espania de Trial” in Becerril de la Sierra, it was inevitable to speak with Manuel Soler again.

The son of Juan Soler Bultó, a cousin of the four times Spanish Trial Champion Ignacio Bultó and the great-nephew of the founder of Bultaco, Don Paco Bultó, ‘El Monstruito’ won four rounds of the Trial World Championship, In Finland with the Bultaco in 1979 and three more with Montesa in 1981. Manuel Soler became the first Spaniard to win a Grand Prix there. In addition, he won four consecutive Spanish National Trial Championships between 1974 and 1977 all with Bultaco; the first of which he was just 17 years of age.

Here is the full interview conducted by Horacio San Martin:

Q – In 2018 this marked the 50th anniversary of the first Spanish Trials Championship. What do you remember from your first participation in it?

Soler: – Perhaps the most relevant thing is that, if I’m not mistaken, I won all the races in which I officially participated. I am undefeated in the Spanish Championship!!

Q – You achieved the first of your four crowns in a row at 17 years old and winning the seven tests called in 1974. Hence your affectionate nickname of ‘Little Monster’? Or have you been baptized before?

Soler: Pere Taulé gave it to me when I was competing out of competition and I was already beating them all. (Smile).

Q – How was the National Championship at its beginning?

Soler: Well, for the manufacturers it was very important. Above all, due to the great rivalry between Bultaco and Montesa.

Q – And what of the sections?

Soler: At that time and with the motorcycles with which we competed… there was everything: easy, difficult, but feasible and not dangerous at all.

Q – What number were you competing with? I say this because in your first races you did it out of competition and with an X as a number because of your young age.

Soler: When they let me run out of competition, I was told to put an X, because in this way, I was identified as a pilot who did not count towards the final classification. When I turned 18 and they let me compete normally, I always wore the number according to my final classification in the championship: one, two, four and six. (Smile).

Q – You did your first events in control of the Bultaco Sherpa T, motorcycles that you knew very well as your father was Juan Soler Bultó, nephew of Don Francisco Xavier Bultó, founder of the firm of the thumb symbol.

Soler: Certainly. At home we were, for obvious reasons, ‘Bultaquistas’, so their models were not strange to me.

Q – Who discovered trial as a sport for you?

Soler: Obviously, I took the first steps with my father.

Q – Did he give you the first advice?

Soler: Yes, the tips and recommendations.

Q – Do you remember any?

Soler: Be yourself and enjoy, which is the main thing.

Q – Is it true that before you could ride a Sherpa T you were piloting a Bultaco Lobito specially adapted for you?

Soler: First they made me some motorcycles with a Mymsa motor and then moved on to Lobito. I remember that they made me a much smaller fuel tank than the original to be able to handle it better.

Q – Do you remember another ‘special fix’ to be able to do a trial with it apart from the tank?

Soler: The truth is yes. In addition to making my fuel tank smaller, they also changed the cylinder capacity. If I remember correctly, first it was 100 cc and in a second phase they raised it to 175 cc.

Q – Did you have a favourite rider at that time?

Soler: At that time, Sammy Miller, because I had been at home training and always saw him with wide eyes. See if he was hallucinating seeing what he was capable of doing with a motorcycle that I remember left some boots pierced with nails in the toe and I put them on to try to imitate him.

Q – Your cousin Ignacio Bultó also won four Nationals, between 1969 and 1972; just two years before your first crown. Were you his most gifted student?

Soler: (Smiles). What I remember is that he always encouraged me a lot when we both went to train. We had a great time. It was great to be able to share with him those afternoons and mornings.

Q – And now that he can’t hear us: who of the two was better?

Soler: (Laughter) At first it was him, but over time… I was!! (More laughter)

Q – He was also successful in other specialties such as motocross and enduro. You, on the other hand, always stayed true to our sport. Why?

Soler: Look, Ignacio liked motocross much more. That’s why, when I started to win and I took over as champion in trials, he told me: ‘Manuel, thank you, because now I can dedicate myself to what I like.’

Q – In 1978 a certain Toni Gorgot arrived and dethroned you. Did you recognize yourself in it?

Soler: The truth is that in the year 1978 I was fulfilling the country and did not have many opportunities to train, so that year it was Toni who took him.

Q – In fact, Gorgot won Bultaco’s last two national titles before it closed the doors in 1980. How did you experience Bultaco’s goodbye?

Soler: Yes. In 1979 he also took it away, but unfortunately, at that time, there was a very difficult situation at home. The future of Bultaco was very dark and the truth is that all that rarefied and unflattering climate did not contribute much to your being able to focus on training and winning the Spanish Championship.

Q – Before all that bad time, luckily, you became the first Spanish rider to win a Grand Prix in the World Championship. It was in Finland in 1979. What do you remember?

Soler: It was unexpected. That day there was no one who could beat me. Everything was coming out!! Even the day before I remember that Finnish television interviewed Yrjö Vesterinen and me, and the reporter’s last question was: ‘Who is going to win tomorrow’? And I, getting ahead of ‘Vesty’, I replied: ‘I’. And look at where in the end I fulfilled it. (Smile).

Q – How did you celebrate?

Soler: There was no representative from Bultaco due to the difficult times we were going through, but I remember that when I got to the paddock Jaume Subirà was there waiting for me with a bottle of cava and ready to shower with it and celebrate the triumph in style. And the truth is that I will always thank him for that nice detail he had for me.

Q – And then Montesa comes in and signs you. How was your arrival forged?

Soler: Well, it was more complicated. I had a verbal agreement with Italjet, but in the end it did not materialize, coinciding with the French GP. However, that weekend, a new window opened. And that I was not in the best condition, since I had a fever and was frankly discouraged. Also, I didn’t start out well. I did a five in the first five zones, and in the sixth it goes and I meet Oriol Guixà, who at that time was the Sports Director of Montesa. Right there he asked me how I was and I then confessed. I exposed all the problems that worried me, as well as the state in which I was. Well, once I finished, he told me that on Monday, the next day, I would stop by the Montesa factory to talk about the possibility of competing with them. Look, his words gave me such a rush that I almost didn’t win. That trial, which was the last one I did with Bultaco, was taken by Bernie Schreiber, but I did second, which was undoubtedly a good end to my career with Bultaco.

Q – The truth is that in Montesa you repeated your Finnish feat up to three more times: in Mura (Barcelona), Austria and Germany.

Soler: The year 1981 was very intense and we even opted to win the World Championship. But in the end it couldn’t be. Of course, it was a very good year.

Q – Was your triumph in the Sant Llorenç Trial your best victory ever?

Soler: Look, unfortunately, not all of them have had the same great importance, but it may be why people remember me the most.

Q – In 1978 we invented a specialty: indoor trial. What do you remember from those first editions?

Soler: That a new era was beginning.

Q – You came second in the second edition of the Barcelona Indoor Trial after Bernie Schreiber. What did you lack to beat him that year?

Soler: Nothing. He was better than me. To tell you the truth, I didn’t really like indoor trials. (Smile).

Q – For those of us who can comb some grey hair, some of those first artificial areas are still very present in our retina: the Pyramids, the waterfall, the quadrilateral, the Tower of Babel … and, of course, the stairs in the middle of the public. What was your favorite?

Soler: None!! (Laughs)

Q – During the first editions of the trial, not a single section was ever repeated. Not even the most popular with fans. Was that good or bad for you?

Soler: It didn’t matter. At least for me.

Q – You were a Montesa rider for three seasons. What was the Montesa of the 70s and 80s like that you met?

Soler: It had its strengths and weaknesses like all motorcycles of that time.

Q – You are one of the few riders who have a motorcycle that bears your name, the Bultaco Sherpa models 158, 159, 182, 183, 190 and 191, in versions of 250 and 350 capacity, called the ‘Manuel Soler’. Would you have preferred that a street in your town or a pavilion was named in your honour?

Soler: (laughs). I also have street!! – since the City Council of Ibi, in Alicante, had the deference to baptize one with my name.

Q – What about Manuel Soler in the Bultaco ‘Manuel Soler’?

Soler: Perfect!

Q – … and later you become an official Merlin rider. You were only one year, since the next you hung up your helmet and boots. How do you rate your stay at the Catalan firm?

Soler: At that time, I already had many problems with my knee. But I think I could do my bit to get Merlin to take his first steps and to evolve his bike. Sadly, a year later my knee problems led me to make this decision to end my sports career.

Q – Luckily, from time to time we see you ‘kill the bug’ taking part in a classics test. You don’t like modern motorcycles?

Soler: Look, I don’t dislike modern bikes, but I find them a bit drastic in their concept for the ‘amateur trialero’ as I am now.

Q – We imagine that you are aware of everything that happens today in the TrialGP World Championship, as well as in the CET. What do you think of both championships today?

Soler: Wrong in their concept to attract the public that in our time came to the trials, but this topic would be to debate it more widely.

Q – Why are they wrong?

Soler: Look. One of the things that we had then was the closeness with the spectators, which nowadays does not exist because all the riders lock themselves in their tents, not allowing access to the general public. Another thing that also influences is the attitude of the promoter in the management of the championship which, like all off-road specialties, is copying the MotoGP formula. For me this is a big mistake, since I believe that each specialty requires a different treatment; it has a different identity. Also in the specific case of our sport we have eight Spaniards in the top 10, which although we like it a lot, the truth is that it reduces the interest of the non-Spanish spectators and fans of the competition.

Q – What recommendation would you give to the organizers of both?

Soler: Difficult to give advice to the organizers when the concepts of the competition, from my point of view, are already wrong at their root.

Q – Are they very different from when you enjoyed them 40 years ago now?

Soler: Yes, different.

Q – Do you still think that the trial has to be non stop?

Soler: No, I think that now ‘the show’ is more important, so from my point of view I would not put fences on the field.

Q – By the way, does the non stop of today look anything like in your day?

Soler: Neither because of the motorcycles we used, nor because of the layout of the areas that are made now.

Q – Do you like the Rating Zone?

Soler: It’s part of the show.

Q – By the way, do you prefer 2 stroke or 4 stroke?

Soler: I’ve always been a 2 stroke lover.

Q – Recently, your time has been occupied by a beautiful project with Jaume Subirà: Subirà Classic Motorcycles. What is it and how is it born?

Soler: Today classic motorcycles and classic trials are experiencing a boom, and it is a nice way to stay involved with the sport with which we have had so much fun and which has given us so much satisfaction.

Q – In more than one interview you have commented that nowadays natural trial is too influenced by indoor trial. Is it still like this?

Soler: Evidently. Indoor trial has had a great influence on the evolution of trial as we know it now.

Q – You have also stated that for you the trial is like a waltz. Who is the pilot who has danced it best for you?

Soler: (Smile). There have been many drivers who did it in the past and many others who are doing it today. (Smile again).

With special thanks to Horacio San Martin of Todotrial for allowing Trials Guru to reproduce the interview in collaboration.

…

Manuel Soler was a popular rider with fans across the world. He was an approachable man with a friendly manner even although he took his riding seriously.

We received the following message and photographs from Madrid trials enthusiast, Luis Munoz-Aycuens Ribas:

“Manuel Soler has been a great trial rider one of the best of the world, a great rider with a smooth and effective driving style.

Manuel was a great man, friendly and open with everybody and his sudden death has meant a big impact on everybody.

During the trial sport life of Manuel, I followed his sporting career with great admiration and interest.

Later in life during the Classic trials of Robregordo and Los Angeles de San Rafael, I met the friendly and open side of Manuel, friend to all and who helped and supported all the riders.

I first met Manuel Soler at the International Six Days Trial held at El Escorial in 1970. The organisation contacted trials riders to help them to route mark, open gates ahead of the riders and maintain the route. One day I was in a team with Alejandro Tejedo (TT rider) and a young Manuel Soler, he was 12 years old, riding a special Sherpa suited for him. At that time the skill and competancy of Manuel to ride the route and the difficult paths was at a very high level. We all enjoyed our tasks in that team.

After this first time, I was following the Manuel career with admiration, respect and a fan, my second important contact with Manuel was in the classic trials of Robregordo and Los Angeles de San Rafael , Manuel every time was very friendly with an open conversation as if we were old friends all our days.” – Luis Munoz-Aycuens Ribas, Madrid

Manuel Soler facts:

Born: 9 March 1957

Died: 20 January 2021 (Cardiac Arrest)

Active with Bultaco: 1974-1970

Montesa: 1980-1982

Merlin: 1983

4 times CET – Spanish National Champion 1974-1977

FIM World Championship Rankings:

12 = 4x 1st positions 2x 2nd Positions 6x 3rd positions

____________________

TRIALS LEGEND – Rob Shepherd

From Farm to Fame…

In 1964 Sammy Miller won the British Trials Championship on his legendary 500cc Ariel, GOV 132. When he moved over to the two-stroke, Spanish made Bultaco the following year, many people thought we had seen the last of the four-stroke trials machines winning the British Championship. The series was dominated by the Spanish until 1977, with Bultaco and Montesa sharing the laurels. Yorkshire farmer Rob Shepherd had ridden the two-stroke Montesa Cota for most of his career, but in 1976 he was approached by Miller to test the Honda that he had developed. He won the British Championship in 1977 and as they say, the rest is history!

Words: John Hulme – Stuart Taylor

Full Credit and original work/text copyright: Trial Magazine UK

Born into a Yorkshire farming family Rob Shepherd was used to finding his way around farm vehicles in the busy environment. When he was fourteen the Wetherby Motor Cycle Club approached his father Alan to ask for permission to use his vast area of farmland at Pateley Bridge, North Yorkshire to run trials on; this was in the late 1960s and trials are still run on the farm to the present day. His first ever trial was on a Greeves Scottish purchased by his father. He made some valiant attempts at the sections and finished the trial black and blue with bruises; at the evening meal on the farm after the event he was so sore he could not sit down at the table to eat – but he had got the trials bug. Seeing his young son have so much enjoyment riding the Greeves on the farm led Alan to buy a brand new Villiers-engined Cotton trials machine. Rob was so excited he spent hour after hour practising on the new trials machine on sections he had marked out on the farm. He soon became a Yorkshire Centre expert at the tender age of sixteen, after taking two novice awards in his first couple of Yorkshire Centre events. He started to enjoy trials so much he progressed to a Montesa and started to ride in National trials to gain experience, and an 11th place in the 1970 British Experts was a superb result. This attracted the attention of Norman Crooks Motorcycles. He supplied the young Shepherd with a new 250cc Bultaco in late November. He would spend the early part of the 1971 season gaining much more experience on the UK trials scene. During this learning period he always had stiff opposition in the form of fellow established “Yorkies” like the Lampkin brothers, Malcolm Rathmell, Mick and Bill Wilkinson amongst others, and this helped to speed up his maturity on the machines and also give him valuable experience in how to deal with the opposition.

At this time he still had to pay for his own machines. John Brise was the Montesa importer before Jim Sandiford came along and it was he who realised Shepherd’s potential and supplied him with a supported machine to join the Montesa team for the Scottish Six Days Trial in May 1971, where he came home in 10th place. At seventeen he won the national Peak and Kickham Trials and came second behind Bill Wilkinson in the famous Allan Jefferies Trial, the one to win in Yorkshire. He also took the runner-up spot to the Irish man Sammy Miller, the man to beat at the time who would later take him under his wing, at the Clayton Trial.

Every Yorkshireman wants to win the gruelling Scott time and observation Trial and Shepherd was no different. He really shot into the headlines when at the tender age of eighteen he won a treasured Scott spoon. He followed this success by winning the Peak Trial yet again, taking the scalps of many of his friends and rivals – Shepherd was on the attack. 1972 would be the year when he was accepted as a true contender for trials honours. He would finish the year with a fifth place at the SSDT and a tenth in the European Championship, but the icing on the cake would be at the super tough Scott Trial. Best on time and observation he took the win in style – a proper Scott win.

A Factory Contract:

This win really brought him into the spotlight, and his reward was a full works contract to ride directly for the Montesa factory in Spain; this would allow him more time to concentrate on practising. With the Montesa Cota in full production Shepherd was now well established in the team. In 1973 he would win the prestigious Pinhard Trophy for the most promising under-21 rider and be a regular top-ten finisher in the majority of events he would enter. Montesa gave him one of the new prototype 310cc machines to help with the development, and at the end of the 1974 season he would move into sixth place in the European Championship. When Malcolm Rathmell arrived at Montesa the machine would be released for sale after further development to become the model Cota 348. In the mid 1970s Rob went through a very poor run of results and Montesa made it clear in 1976 that his works contract would not be renewed for the next season. The Suzuki trial’s project was in full swing and it was they who made enquires to see if Shepherd would be interested in riding the new machine. Word soon started to circulate on the trials scene that he was on the lookout for a move of machine and this spurred him on and his results improved, and at the season close he won the British Experts.

Good friend Nick Jefferies suggested he try the four-stroke Honda he had been helping to develop with Sammy Miller. Miller took one of the machines which had been ridden by Brian Higgins (Miller did not renew Higgins’ contract with him for 1977), to the Pateley Bridge farm for Shepherd to try. After winning the experts Montesa had a change of heart and offered him an improved contract, but after the ride on the Honda his mind was set and he signed to ride the Honda in the Miller team. He instantly came to grips with the unfamiliar four-stroke’s characteristics right from the start; he was amazed at the Honda’s tractability, cleaning sections he could never manage on the two-stroke Montesa.

He took his first Honda win at an Eboracum Club trial early in January 1977, and to prove to the optimistic pundits that he had mastered the four-stroke technique he won the season-opening national Vic Brittain Trial, the first four-stroke national trials win for 12 years; Miller was over the moon. The machine Rob was ridding was the Ex Brian Higgins long-stroke, the one he had tested, he loved it! He followed this win by taking the opening British Championship round win at the Colmore Cup; Honda were leading the British Championship!

Honda Japan was following Shepherd’s results with a keen interest and sent him a brand new short-stroke version of the machine. The new red and white machine was debuted at the St David’s British Championship round in Wales, finishing in joint third place. In the World Championship events his form was nothing special and he secretly had a desire to return to the older long-stroke. He did this for the Belgium world round and his results instantly improved as he came home fourth.

Shepherd’s SSDT efforts in May would deliver fifth place. His confidence was now on a high as he demonstrated the unique four-stroke machine’s potential to its full, winning the British Trials Championship and also achieving the first ever win for a four-stroke trials machine in a World Championship event in Finland, as he finished the world series in fifth place after a superb set of results as the season concluded – what a year! Talking about the 1977 World Championship campaign years later he commented, “Martin Lampkin once told me never to leave a winning bike and he was correct, as my results went off the boil when I started riding the short-stroke. If I would have stuck to the long-stroke and done the American and Canadian rounds it might have changed the whole season”.

Bombshell!:

After celebrating the British Championship success Miller dropped one of the biggest trials bomb shells ever – Honda were pulling out of trials, his three year development plan was over! Miller had known about this decision before the end of the British Championship but he handled it in his usual dignified professional manner and kept the news away from Shepherd.

At the time Miller was very upset by the pull out and Shepherd could not believe it after delivering Honda the British Championship. The factories were soon after the much sought-after signature of Shepherd on a works contract to ride their machines. He flew out to Italy to test the new SWM and Montesa offered him the number one team berth as Malcolm Rathmell signed for Suzuki.

Shepherd would not sign any contracts though as he had an ace card up his sleeve he was not ready to play. Jim Sandiford wrote to him with an improved offer but he wrote back to once again turn the offer down, saying he had been made a better offer elsewhere; Sandiford was bemused. In early 1978 Rob had no contract and all the works Honda engines had been collected from the Sammy Miller Empire. Shepherd then dropped his own unexpected bombshell; he would still be riding for Honda in trials!

Eight weeks after Honda had made the decision to pull out of trials they were back. The boss of Honda UK, Gerald Davison, would use some of his race budget to support Shepherd with two bikes and three engines, as well as covering other expenses to ride in the British Championship, World Series and other selected events such as the SSDT and Scott Trial on a one year deal. He would also supply a mechanic; Mike Ember Davies from the racing department would keep the Shepherd machines in good running order. His old machine he had been riding during 1977 was now a little long in the tooth and needed replacing.

Word had filtered through that a new machine was being built in Japan. The new machine, a 359cc in fire engine red looked the business but turned up only a few days before the SSDT. He had little time to practise on the machine but came home in a solid fifth place. The year would go pretty much to plan but there were some problems with the new development machine which kept him down the results, though runner-up in the British Championship and fifth in the world was just reward for his efforts. His heroics in the Scott are what legends are made of. He was pushing hard when he crashed the Honda towards the latter end of the event, putting a hole as big as your fist in the fuel tank. He manfully struggled on, ignoring the fuel covering his riding kit and running out of fuel in sight of the finish to push the Honda home in a gallant third place.

In the closed season at the end of the year he was promised a new machine and contract for 1979, he would also keep the services of a mechanic. He flew to Japan for a 12 day visit to test the new machine. He rewarded all the hard work and commitment from Honda when he won the opening world round in Ireland, but the machine was now becoming unreliable. A week later at the UK world round he slumped to 12th place after ignition problems. The new machine he had tested duly arrived in time for the SSDT. It was a very confident Shepherd who headed to the highlands for the trial. He set off superbly, finishing the first day in second place before moving into the lead on the Tuesday. He would drop to second again on the Thursday before moving back to first on the Friday – would he win? The answer was no as he dropped to fourth place at the finish; his riding number had put him at the front of the entry for the final day putting him at a distinct disadvantage.

The rest of year went well as he dropped just one place in the world standings to sixth and came home fourth in the Scott. In the British Championship he also dropped down to third place due to the machine problems with the old bike earlier in the year. 1980 would be a frustrating year as he took the Honda to third at the SSDT, a superb result. As the year progressed he became tired of all the travelling and preparation needed to succeed at the highest level. He could still raise his game though, taking a British Championship win and third at the Scott. He sensed that with the young hot shot Belgian rider Eddy Lejeune on the scene his Honda days would soon be over.

Staying Japanese:

His last ride on the Honda was at the British Experts Trial, which he retired from when he damaged his knee. Honda told him his contract would not be renewed and he officially retired from World Championship competition. When the news broke Shepherd once again became hot property on the race to get him to sign to ride for another manufacturer. John Shirt Snr had taken his Majesty Yamaha machines to the heights of a world round win with trials legend Mick Andrews, so he knew the machine could perform at the highest level.

With Yamaha taking much interest in the project and with the Majesty partnership wanting to sell more machines Shirt Snr spoke to Shepherd to see if he wanted to test a machine in secret for two reasons; one he would be able to get a top rider’s opinion on the machine’s performance, and it would also give him the chance, if Shepherd liked the machines, to talk about a contract to ride in the 1981 British Trials Championship. The test took place at the famous Hawks Nest venue close to Shirt’s Buxton base. He took three different machines for Shepherd to try, all in different states of tune, and Rob brought his brother Norman along, a top rider in his own right, to get his opinion. The test went well and the two brothers took a machine away with them to try while Shirt modified another machine to include all the suggestions Shepherd had made. After further tests the two brothers signed with Shirt to ride the machines in the British Championship and selected trials, including the SSDT and Scott Trial. Shepherd knew he would find it difficult to adapt but worked closely to find a setting he liked. In his first major outing at the Colmore Trial he finished second after a late five mark penalty when he put his foot on the throttle cable, dropping him to second.

In the first two world rounds in Ireland and the UK he finished 20th and 27th, finally accepting the World Championship glory days were over. He retired from the SSDT when a family problem meant he had to return home. The rest of the year would witness some promising results including a fourth at the Scott but at the end of the year he retired from the sport. He would initially ride in local trials on a Bultaco just for fun but would eventually stop riding altogether. In all he had won over 40 national trials in a career lasting thirteen years. He would keep an interest in the sport as trials were still held on the family farm, but the days of hearing Rob Shepherd on the four-stroke Honda would remain a lasting memory.

Copyright details:

© – ‘Trials Legend – Rob Shepherd’ – Article: Trial Magazine UK / CJ Publishing – 2016

TRIAL MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTIONS LINK : HERE

___________________

© – ‘Trials Legend – Bernie Schreiber’ – Article: Sean Lawless / Lawless Media – 2018

___________________

© – ‘Trials Legend – Manuel Soler’ – Article: Todotrial / Horacio San Martin – 2019

___________________

Additional text, material and comment: Trials Guru/Moffat Racing, John Moffat – 2021 (All Rights reserved)

© – Images copyright and courtesy of:

- Trial Magazine UK

- Eric Kitchen (Worldwide Copyright)

- Claudio Pictures – Copyright: Jean-Claude Comeat, France

- Len Weed, USA

- the late Manuel Soler, Barcelona

- Luis Munoz-Aycuens Ribas, Madrid

- Colección Hermanos Lozano, Spain

- Blackburn Holden III, Yorkshire, England

- Alain Sauquet

- Chris Sharp Photography, Belfast

- John Honeyman, Markinch, Scotland

- Iain Lawrie, Kinlochleven, Scotland

- Colin Bullock/CJB Photographic

- Rhosalyn Price, Abergaveny, Wales

- Graeme Campbell, Moffat, Scotland

- Motocat, Catalunya

…